Document details

Abstract

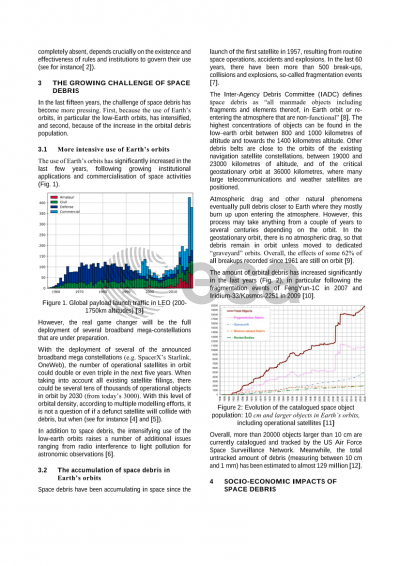

In the context of increasing activities in outer space, this paper explores selected long-term sustainability issues, with a particular focus on the economics of space debris. Several international organisations and committees, national administrations and space agencies have already carried out extensive work on the legal and technical aspects of space debris and the congestion of low-earth orbits. This paper brings in some original perspectives on space sustainability, by providing a fresh look at the economics of space debris, and by proposing to decision-makers some avenues for action, based on experiences in environmental pollution abatement from other policy domains.

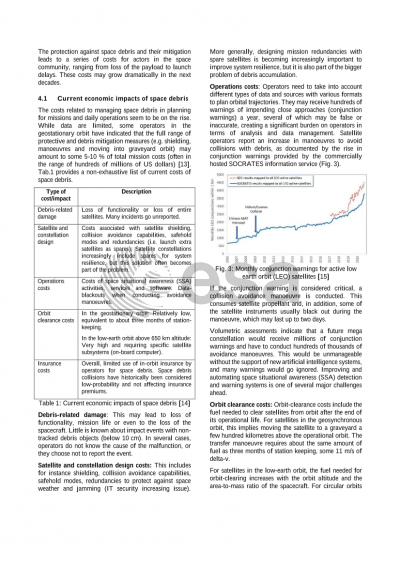

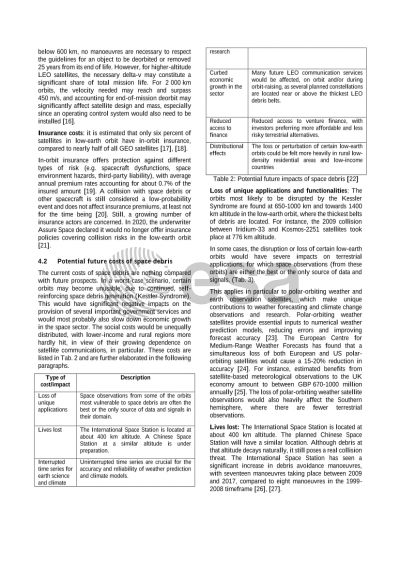

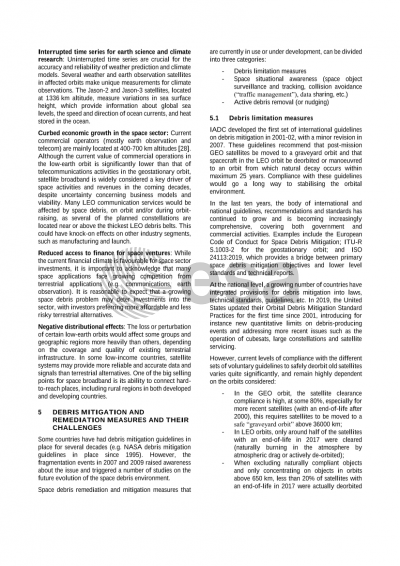

Space debris already generate associate costs, including satellite protection, mitigation and even replacement costs in some cases. To this, the costs of debris surveillance and tracking must also be added. Operators in the geostationary orbit have estimated protective and mitigation costs at some 5-10% of total mission costs. In the upper lower-earth orbits, these costs are deemed much higher.

However, the main risks and costs lie in the future, if the generation of debris spins out of control (i.e., the Kessler Syndrome). This ecological tipping point may render certain orbits unusable and, under this scenario, socio-economic impacts could be severe. Several important space applications could be affected or lost; notably space-based observations for weather forecasting, climate monitoring, earth sciences, and potentially, satellite communications. Certain geographic areas and social groups would be disproportionally affected, in particular in rural areas with limited existing ground infrastructures and large reliance on space infrastructure.

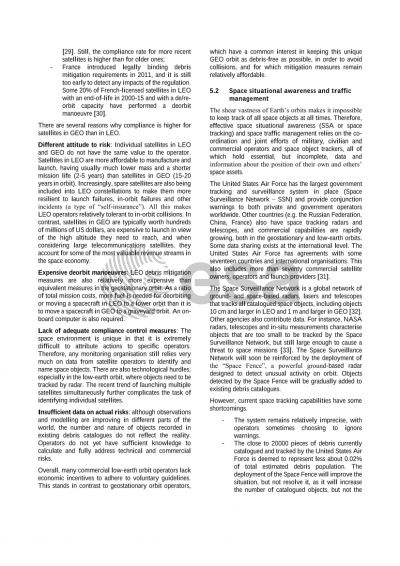

Comprehensive national and international mitigation measures exist, but compliance is insufficient to stabilise the orbital environment. While most GEO operators comply with guidelines, compliance rates are much lower in LEO (less than 60% in all orbits and closer to only 20% in orbits above 650 kilometres). There are multiple legal and technological challenges to debris mitigation and remediation. Legal issues concerning debris ownership, liability and long-term funding of operations are far from being resolved. Furthermore, with current space situational awareness capabilities, it is extremely difficult to attribute actions to specific operators.

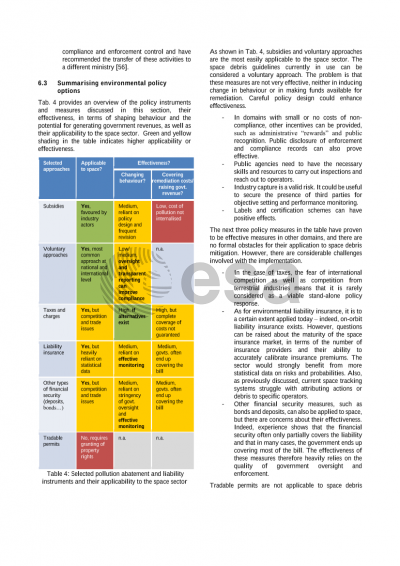

Improving compliance behaviour among satellite operators is an indispensable step to contribute to long-term sustainability of orbits. For this, a range of policy solutions and lessons learnt from other domains and sectors may serve as inspiration, in particular common pollution abatement measures, with instruments that include taxes, tradable permits, financial security mechanisms, and voluntary agreements.

Other relevant avenues for action could include the strengthening of space situational awareness (SSA) systems, data reporting structures, engaging in further R&D in debris removal and remediation; and finally addressing debris mitigation guidelines compliance particularly at national levels. This will imply close co-operation with public and private actors. In order to support and improve decision-making, the development of new indicators should also be explored, in order to monitor debris mitigation performance and environmental instability.

This paper is the result of work conducted by the OECD Space Forum and their eleven partnering organisations: The Canadian Space Agency (CSA), Canada; Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES), France; Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR), Germany; Agenzia Spaziale Italiana; (ASI), Italy; the Korea Aerospace Research Institute (KARI), Korea; the Netherlands Space Office, the Netherlands; the Norwegian Space Agency and the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, Norway; the Swiss Space Office, Switzerland; the UK Space Agency, United Kingdom; National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (Office of Strategic Engagement & Assessment), United States; and the European Space Agency (ESA).

Preview