Document details

Abstract

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the problem of orbital debris was raised, and subsequently studied and addressed, when the number of operational spacecraft represented only a modest fraction of all objects, typically larger than 10 cm, cataloged by surveillance systems. This situation basically continued over the next four decades until around 2020, a period during which recommendations, guidelines, standards, and laws for space debris mitigation were developed and gradually implemented, both nationally and internationally.

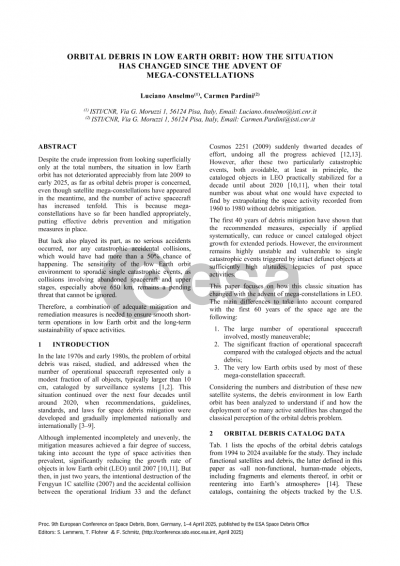

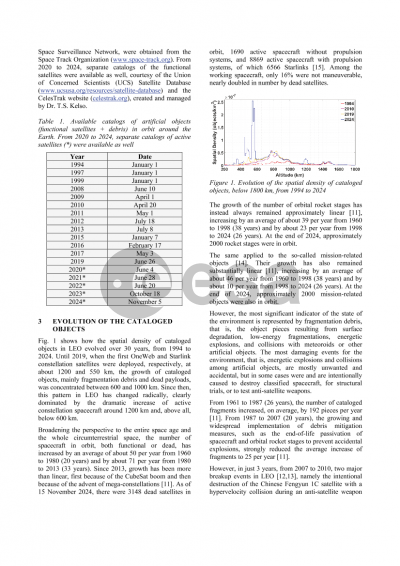

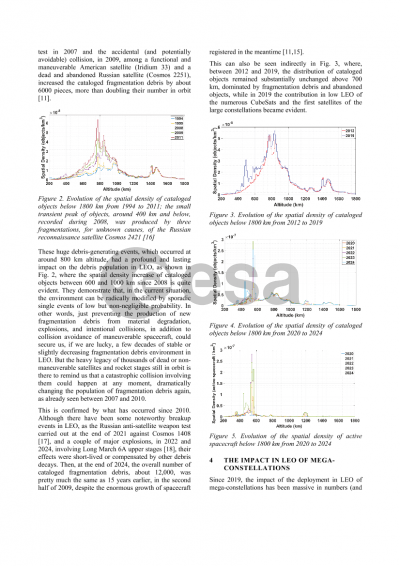

Although implemented incompletely and unevenly, the mitigation measures achieved a fair degree of success, taking into account the type of space activities then prevalent, significantly reducing the growth rate of objects in low Earth orbit until 2007. But then, in just two years, the intentional destruction of the Fengyun 1C satellite (2007) and the accidental collision between the operational Iridium 33 and the defunct Cosmos 2251 suddenly thwarted decades of effort, undoing all the progress achieved. However, after these two particularly catastrophic events, both avoidable, at least in principle, the cataloged objects in low Earth orbit practically stabilized for a decade until about 2020, when their total number was about what one would have expected to find by extrapolating space activity from 1980 onwards, without debris mitigation.

The first 40 years of debris mitigation have shown that the recommended measures, especially if applied systematically, can reduce or cancel cataloged object growth for extended periods. However, the system still remains highly unstable and vulnerable to single catastrophic events triggered by intact defunct objects, legacies of past space activities at sufficiently high altitudes.

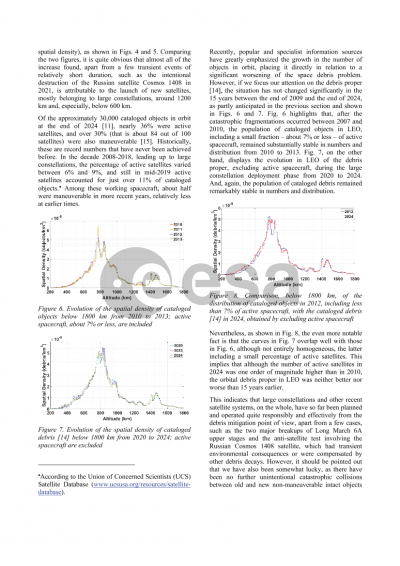

This paper focuses its attention on how this classic situation has changed with the advent of mega-constellations in low Earth orbit. The main differences to take into account compared with the first 60 years of the space age are the following: 1) The large number of operational spacecraft involved; 2) The significant fraction of operational spacecraft compared with the cataloged objects and the actual debris; 3) The very low Earth orbits used by most of these mega-constellation spacecraft. Taking into account the actual numbers and distribution of these new satellite systems, the debris environment in low Earth orbit has been analyzed to understand if and how the deployment of so many active satellites has changed the classical perception of the orbital debris problem.

In the past, the focus was mainly on the long-term preservation of the environment, trying to limit the number of catastrophic collisions, in particular at altitudes where air drag is ineffective in removing the fragments fast enough. The deployment of mega-constellations, especially at relatively low altitudes, has quite obviously shifted the attention to short-term collision avoidance and space traffic management issues. However, although in some respects, the problem of space debris proper may not have worsened since the advent of mega-constellations, the vulnerability, and sensitivity of the low Earth orbit environment to sporadic catastrophic collisions remains a pending threat that cannot be ignored.

Preview